|

| In Derry, most people can't forget the past. In Britain, some people don't even know it. |

Are the Irish an over-sensitive lot?

Is it really worthy of a national debate – and even a Twitter tag – when a British TV presenter goes on social media to tell us that some of us “need to get over ourselves”?

And all because he described a row between the British and the Irish over the impact ‘Brexit’ will have on the Irish border as a “kerfuffle” in an interview with the Irish Tanaiste (or Deputy Prime Minister)!

The online reaction to a Twitter outburst by Sky News presenter Adam Boulton might have been something of a storm in a tea-cup this week, but it comes at a time when Irish people are deeply alarmed by the attitudes they are hearing from some people on the other side of the Irish Sea.

Not to mention general disquiet over the impact Brexit will have on the Irish economy, particularly in border communities which were devastated by 30 years of The Troubles until the 1998 Good Friday Agreement brought wonderful changes to all of our lives.

The Republic exports €15.6 billion worth of goods to the United Kingdom each year and will have the only land border between the UK and the European Union once the Brexit divorce proceedings are completed.

As is often the case when a small country is located next to a much bigger neighbour, the Irish know far more about the British than the people on the bigger island do about the Emerald Isle.

Thousands of Irish people make the short journeys to Britain each week to cheer on the footballers of Liverpool, Manchester United, or Arsenal, often to the detriment of their local soccer clubs.

Thousands more love soap operas such as ‘Coronation Street’ and ‘East Enders’ and follow the gossip involving British celebrities through tabloid newspapers and magazines which circulate widely in Ireland.

It might be hard to believe, but some people even talk about the British ‘royal family’ around the water coolers at their workplaces.

|

| Adam Boulton's remarks about the Irish kicked up a storm |

The engagement of a British prince can generate headlines in Irish newspapers, without a hint of irony, whereas many people in the UK would struggle to identify the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, if his photo appeared in a glossy magazine.

Given the vast differences in population between the two countries, Britain has 65 million citizens compared to 4.7 million in the Republic, it is no surprise that British TV is widely watched on the other side of the Irish Sea.

Until the recent “kerfuffle” over the impact Brexit will have on the Irish border, it’s fair to say that relationships between the two countries were never better than we have seen over the past two decades ago.

The Good Friday Agreement brought peace, respect for diversity, and guarantees for the Unionist population in the north-east of the island that they won’t be steamrolled into a United Ireland against their will.

It also brought about the demolition of the hated border posts and checkpoints, opening up the joys of the North to tourists for the first time.

Until the mid-1990s, tourists were virtually unheard of in Northern Ireland. Now Belfast is seen as one of the best cities to visit in the world and thousands visit to explore the landscapes made famous by 'Game of Thrones'.

Times have changed since the only time Northern Ireland made the UK news was for bombings or shootings and people in London used to warn tourists to stay well clear of the province.

Relationships have changed beyond all recognition. How much things have improved was evident in the State visit by Queen Elizabeth to Ireland in 2011.

|

| Northern nationalists feel they have been forgotten or abandoned post-Brexit |

People were surprised, shocked even, by the warm welcome the British monarch received during her three day visit, given the symbolism attached to royalty throughout hundreds of years of colonisation.

But the relationship between Britain and Ireland has never been black and white and up to six million people in the UK have at least one Irish grandparent.

Like the US, Canada, and Australia, Britain has often provided a ‘safety valve’ for a land which has seen so many of its children emigrate to forge out brighter futures.

In the 1950s and again in the 1980s, when Ireland failed to provide hope to so many of its people, thousands upon thousands of Irish people poured into British cities in search of new lives.

Almost everyone on the island of Ireland has some family connections to Britain. In the European Union, the British were often the Irish people’s closest allies as two English-speaking islands on the western periphery of the continent.

But, since the shock of the Brexit vote in June of last year, many Irish people have become alarmed by some of the language they are hearing from across the Irish Sea.

Throughout the Brexit debate, there seemed to be barely a mention in the British media over the implications there would be for communities along the Irish border if the UK was to leave the EU.

A tabloid editor told our Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, recently to “shut his gob” even though this issue has massive implications for Ireland for generations to come.

We have heard people wonder why Ireland does not also leave the EU, or even why we don’t rejoin the UK – as if they are totally oblivious to the terrible history of conflict, oppression, and suspicion between the two countries going back over 800 years.

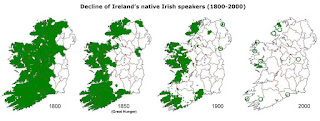

We have been shocked to hear people celebrate our common language, with not a semblance of understanding of the way in which the British authorities went about killing off the Irish language over two centuries.

|

| A graphic illustrating the decline of the Irish language. |

Not many British people would be aware that, under the Penal Laws, it was illegal for Catholics to teach in schools between 1695 and 1782. Education through Irish was confined to 'hedge schools' until the 1840s, when the Great Famine took the lives of a million Irish people.

Just this week, 200 nationalists across Northern Ireland wrote a letter to the Irish News to express how alienated and abandoned they feel in the era of a Brexit vote which was rejected by 56% of voters in the province.

At a time when the Democratic Unionist Party holds the balance of power in London, their letter came as a grim reminder of the sectarian state which treated Catholics as second class citizens from partition in the 1920s until the eruption of the Troubles in the late 1960s.

Nobody wants to see a return to those dark days and perhaps it is true that the Irish cannot forget their history of famine, deprivation, and emigration.

But sometimes Irish people get the feeling that their counterparts in the UK are totally oblivious to their own country’s history of oppression and occupation in Ireland.

Respect works both ways. One land cannot seem to forget its past, and the other sometimes shows that it knows nothing about it.

A throwaway remark by a Sky News TV presenter might have generated an over-reaction and, yes, perhaps Irish people need to lighten up a bit and leave our sense of victimhood behind.

But the loudest Brexit supporters in Britain, who did not seem to have a concrete plan for life after leaving the EU, should not be so surprised that people in Ireland have massive concerns over the impact which their vote will have on all of our lives.

Check out my business website at http://ciarantierney.com/

Ciaran Tierney is a journalist, blogger, and digital storyteller, based in Galway, Ireland. Find him on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/ciarantierneymedia/

Find Ciaran Tierney on Twitter, https://twitter.com/ciarantierney