|

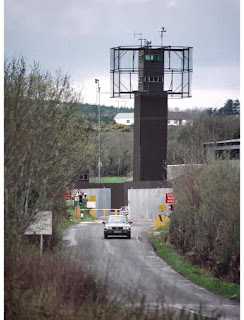

| A mock border post brings of a reminder of more troubled times |

It’s never nice to feel that you are an irrelevance, that your very existence does not matter and that your views are better left ignored.

It’s never nice when things most people take for granted – security, safety, the freedom to pop out to the shops or to enjoy a night out on the town – are being threatened by people who are oblivious to the impact their politics have on other people’s lives.

And it’s pretty appalling when the people who threaten your fragile peace have little concern for history or the true consequences of the damage they are about to cause.

In the US, President Donald Trump’s obsession with a wall disrupted the government for weeks and provoked tensions across the land.

In the border communities of Ireland, older people in particular know all too well about the divisions caused by walls and the trouble they cause.

A hard border is the last thing they want to see in the small towns and tight-knit rural communities where life has been utterly transformed, for the better, over the past two decades.

I remember a Belfast lady once telling me, with a sense of wonder in her voice, that her mother had spotted two Japanese tourists in the vicinity of City Hall. That was 1996, hardly a lifetime ago.

But it was a very different land.

|

| Checkpoints dotted the landscape until the 1990s. Photo: Carly Bailey, via Facebook. |

Local people remember the checkpoints, the watchtowers, the military helicopters, the barbed wire fences, and the soldiers brandishing machine guns along the Irish border.

How a short ten minute drive to the supermarket in Strabane, Crossmaglen, or Newry could turn into a two hour nightmare, with long queues, intolerable delays, guns being brandished and hostile interrogations at the side of the road.

They have to tell their children that a seemingly uneventful or boring life is so much better than a life defined by fear. And remind them that there was a time when 3,600 people lost their lives because of walls, barriers, and the conflict between two opposing tribes; when it was simply too dangerous to cross the city at night.

Back then, a mother in Derry or Belfast could only dream of the carefree attitudes of parents in Donegal or Dublin when they watched their teenage children head out for the night.

As a child, a trip to the shops involved British soldiers pointing machine guns at my dad. The only British people we knew wore military uniforms and mothers cried at night that this was no place to bring up a child.

When I was a youngster, one of my best friends had part of his hand blown up by a British Army grenade. It had been discarded, casually or wrecklessly, in a field near our homes. It prompted my tearful mother to beg my father to move back to Galway. No border community deserves to witness those kind of scenes again.

People remember the celebrations in 1998, when we thought (no, we were sure) we had left all those dark days behind. The Good Friday Agreement guaranteed peace and prosperity to everyone – for the unionists, there was the guarantee they would not be railroaded into a United Ireland against their will; for the nationalist minority, a guarantee they would never be treated as second class citizens in a sectarian state again.

|

| The horror of Bloody Sunday alienated nationalists in Northern Ireland and drove many young people into the arms of the IRA in Derry |

In just a few months, we have seen so much optimism evaporate.

It is unimaginable that the simplest of journeys could be fraught with danger, bureaucracy, and security concerns again. But people are having to face those fears again.

The majority of the people in Northern Ireland did not vote for Brexit. The people who live along the border are now being told they should have no say in a decision which could have such drastic implications for their lives, by politicians in London who have no understanding of the reality of their lives.

They are being asked to forget that Northern Ireland came into being in order to create an artificial pro-British majority, meandering through villages and rural communities who would be cut off from their own hinterlands.

For 21 years now, they have been able to live peaceful, normal lives. The Queen of England might still appear on their pound notes, but a trip to Donegal, Cavan, or Monaghan is no longer fraught with danger, lengthy interrogations, or fears of exploding bombs.

As British politicians continue to discount and dismiss their fears, people who live and work along the barely visible border are expressing and hearing growing, frantic concerns.

There are farmers who proclaim they would dismantle the hated checkpoints or turn a blind eye if their neighbours took out guns – but their fears, concerns, and frustrations are rarely heard in the corridors of power in London.

In recent weeks, Irish people have had to deal with their elected leader being described as a “liability” in the British press.

A tabloid newspaper, infamous in the past for its anti-Irish venom, said that Taoiseach Leo Varadkar would “deserve much of the blame” for the “misery and chaos” a No Deal Brexit would cause to the Irish people.

|

| Anti-Irish venom is all the rage in the UK tabloids again |

All for reflecting the fears of people living all along the border, that a vote which had nothing to do with them would have a drastic impact on the quality of their lives.

People in the Republic had absolutely no say in the Brexit referendum, but they are already being blamed in case it all goes wrong and the British go crashing out of the European Union without any kind of a deal.

People in Fermanagh, Derry, or Tyrone were seen as an afterthought, an irrelevance during the 2016 Brexit campaign.

But the people who have real life experience of a 'hard border' have a right to be frightened that the violence which scarred so many lives could be set to return. Even though they are being told by those who haven’t a clue, or no memory of living through terrible times, that there is no need for concern.

It’s clearer than ever now that many of those who voted for Brexit could not have cared less about the implications for the people who live alongside the 200 border crossings on the 300 mile frontier which divides the island of Ireland.

|

| A protest against Brexit along the Irish border |

Pro-Brexit British politicians like Jacob Rees-Mogg, Nigel Farage, and Boris Johnson tell the people living along this invisible line that they are being over the top in their opposition to the prospect of the return of border posts and checkpoints to their small rural communities.

But none of these jingoistic ‘Brexiteers’ has ever explained to those who live along the border how the UK can make new trade deals across the globe, and have different tariffs and agricultural standards, without huge disruption to their lives.

How convenient it is to forget that, for almost a century, the border in Ireland has been an artificial line – designed almost a century ago to maintain a contrived ‘pro-British’ majority in the north-east corner of the island.

How convenient it is to forget that 56% of the people of Northern Ireland voted against Britain leaving the European Union in the shock 2016 poll.

We keep hearing about the 17.4 million who voted for Brexit, but not so much about those on the island of Ireland who had huge concerns about being cut adrift from the rest of the island.

We keep hearing about the pro-Brexit Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), who have held the balance of power in London since the last General Election, but far less about the farmers and small businesses whose livelihoods have been placed under a severe threat by the return of walls, checkpoints, and the return of a hard border.

We keep hearing about how the DUP even turned down a special deal for Northern Ireland, because holding on to their British identity seems to be even more important than the economic prospects of the people they represent.

And we hear so little of the alarm in small towns and villages over the threat to a fragile 20-year peace because old divisions and animosities have never really been resolved.

|

| In Belfast, the history of a terrible conflict is painted on the walls Photo Ciaran Tierney Digital Storyteller. |

Belfast is a great place to visit these days, but they still close off the roads along the ‘peace walls’, which split divided communities, late at night. When tour guides joke that they cannot go for a pint on the other side of those walls at night, they are not really joking at all.

Old tribal divisions and hatreds are still hidden away just behind those walls.

A few miles away, along a once bitterly disputed border, tourists hardly even realise when they are crossing from one part of Ireland into the other.

But the local people know, understand, and remember. With Brexit now less than two months away, there is a growing sense of alarm over the prospect of seeing the hated checkpoints, armed soldiers, and watchtowers return.

There is still a terrible fragility to the Irish peace process, even after 21 years of peace, a fragility which becomes all the more disconcerting the more the fears and concerns of those who are most affected by a hard border are being denigrated and ignored.

* Ciaran Tierney won the Irish Current Affairs and Politics Blog of the Year award at the Tramline, Dublin, last month. Find him on Facebook or Twitter here. Visit his website here - CiaranTierney.com.

* If you would like to hire a professional journalist to blog for your website, you can get in touch at ciaran@ciarantierney.com

|

| Ciaran Tierney with the Irish Blog of the Year award |

My grgrgrandfather sailed from Tyrone to Canada with 5 young children in 1867. I initially couldn't find him on the passenger list with his family, then found him at the end of the list, the last one who boarded the ship. I assume he was last because he may have been saying goodbye to his four older children left behind. He survived the famine years and God only knows what they suffered and saw as Catholics.I cannot imagine the anguish as they left their families and homeland behind. And now 2019, nothing is resolved. So sad.

ReplyDelete